The third session of the Course on “The Business and Economics of Space” was on Thursday, Nov 11. This time the topic was the Financing of the Commercial NewSpace Industry. You can find my earlier posts on the first two sessions here and here. This post will contain not just what was covered in the course but also my personal opinions of the various financing options available to a NewSpace venture.

The key takeaways were in the following areas

– The funding cycle of high Growth Businesses

– Private Market Financing options such as Angels, VC and PE

– Public Market Financing alternatives such as IPO, SPAC and Direct Listing

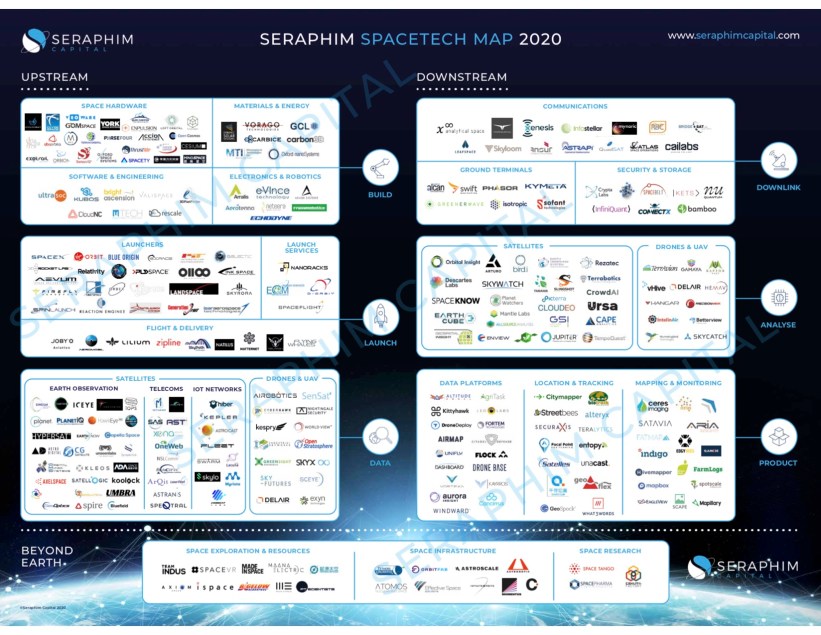

First, lets take a look at the activity in Space Financing in 2020. The chart below shows that $7.6B (all figures in US$) was invested in start-up space companies. We are seeing more funding, to more companies from a bigger pool of investors than ever before. Almost two thirds of the investment comes from Venture Capital Firms. More on Space VC’s later.

The bulk of the funds went to a handful of companies ; SpaceX, OneWeb, Relativity etc as their follow on rounds were larger and larger.

If we look at the trends over time, two things become apparent. The magnitude invested in start-up space companies was fairly stable from 2015 to 2018 and then exploded from 2019 to now. Public offerings also entered the mix with Virgin Galactic going public via a SPAC deal in 2019 leading to an explosion in space firms going public.

At each stage of a start-up companies life, there are financing options that are appropriate to their needs. Each option has trade-offs, positives and negatives that can influence the founders or company’s management on deciding which way to go. The next chart highlights investment options such as Angel investors, VC’s, Private Equity, Corporate money, Banks and Public Markets.

Initially, a start-up is usually boot-strapped by its founders. All of my companies; AurorA, Amitel, AMI Telecom etc were all boot-strapped as I chose to never take outside investment. All growth was funded from internal cash flow. Obviously that is a constraint , but it also fosters self-discipline. Conversely , I was able to retain 100% of the equity as well as 100% of the decision making. Once a company takes outside investment, the management is responsible to make decisions for the welfare of all the shareholders. Some of those shareholders may demand representation on the Board of Directors and may have a vision for the company that is not aligned with what management would like to see.

Raising less money, or raising it later in the company’s timeline can lead to better outcomes. Industry dynamics play a key role as a analytics based SaaS space business is very different from a capital intensive hardware based space business. Taking investment capital too soon, with too much dilution can lead to poor consequences. In theory, VC’s should provide no only cash but validation as well and also guidance such as advice, connections and resources. Choose your VC partner wisely though, because VC’s take big bets on risky companies because they want a big payoff.

If we look back at the chart, you can see that each form of financing has a typical lifetime or exit horizon. Angel money typically comes from “Friends and Family” or Seasoned Investors that have been in the sector of your business. It is patient money, not looking for a quick exit; usually it is heavily invested in the dream of the founders to see the venture succeed .

VC firms operate on a different model. They raise funds from a group of limited partners with the intent in investing in a selected group of very high, very fast growth companies. The fund will typically be wound up in six to eight years and the portfolio operates according to a power law rule i.e. one or two home runs (10x to 30x) from a portfolio of ten to twenty companies. Taking money from the wrong VC could be disastrous; they may push management for insanely fast growth at all costs.

For the investors to make money, they have to be able to exit the investment. If an exit comes up for a venture backed company, say an acquisition offer from a strategic buyer or corporation that would let all parties have 50% returns, the VC may not be interested and veto it (if that right is in their term sheet). Such an exit would have little impact on their portfolio. Often VC’s operate from a “go big or go home” mentality which may be at odds with the management team’s desires.

Space companies tend to be very capital intensive by nature. Whether a launch company, a satellite constellation Earth Observation company, or any form of antenna or Earth Station network provider, often times a very significant upfront capital investment is required before any revenue is seen. If we look at the chart above, the business financing cycle for a typical company, for a space company that Valley of Death is often much deeper and extends much longer into the timeline. Thus they are riskier investments with long time horizons.

Ideally, each stage of investment raised by the start-up company is deployed to make the whole venture more valuable. Angel and seed money let the founders prove the concept. The Series A will fund them enough to be able to retire some risk, perhaps technical risk. Another round may validate the product market fit, or scale up. At each stage the valuation should be growing to be able to justify the dilution of taking on additional investment.

Continuing on the venture backed path, or taking money from private equity investors can work for a space company. Staying on that path has costs too; like everything in life there are tradeoffs. There is the obvious dilution from each VC round raised as well as more and more restrictive terms and covenants. The CEO and CFO may find they are on a constant treadmill of fundraising, spending most of their time raising capital rather than growing the business. Running out of cash means death, so you have to keep meeting milestones to justify the next round to keep extending your runway.

The final point about VC’s ; choose your VC partner carefully. You want one that has loads of Deep Tech or SpaceTech experience, that can truly provide the advice, guidance and networking I mentioned above. Seraphim Capital or Promus Ventures are two good examples of VC’s with deep sector experience. Vinod Khosla, founder of Khosla Ventures, has said that most VCs “haven’t done sh*t” to help startups through difficult times, and he estimated that “70% to 80% percent [of VCs] add negative value to a startup in their advising.”

At some point it makes sense to look at taking the company public. This means listing the company on a public stock exchange like the NASDAQ, NYSE, TSX or LSE. This can be done with an Initial Public Offering (IPO), Special Purpose Acquisition Fund (SPAC) or Direct Listing.

Operating as a public company requires a lot of preparation from the management team. They have to be ready for the public scrutiny, as their financial results will be reported to the public every quarter. They will need to ensure their past financial results are fully audited and meet the proper accounting standards. Often the C-Suite team will need to be augmented with new hires familiar with the rigour of operating as a public firm including investor relations, communications, human resources let alone an experienced CFO and legal counsel.

But the advantages are numerous. First, being public provides liquidity for the shares. Not only is there an exit for previous investors, but you can provide employees and management with stock option based compensation that is readily cashable. Future fundraising is far less onerous once you are public as you can tap the debt and equity markets easier. If your business strategy involves acquisitions then the company can use its shares as currency for the transaction, retaining precious cash.

The IPO process can be very onerous and time consuming. After preparing the company in a process that can take up to a year, and a time sucking roadshow, the investment bankers retained decide upon a valuation for the company and a share price. Often times even the best banks can be off on what they expect the public to see as fair valuation for the company. Thus there is no guarantee for the amount of money that can be raised in the IPO. The end result can be disappointing a) for not raising sufficient funds in the IPO or b) for underpricing the offering and leaving too much value on the table.

SPACs offer a different and faster route to go public that have some very unique features that are very advantageous , especially to a space firm. The SPAC sponsor team sets up what is known as a blank cheque company on the stock exchange . The SPAC files with the SEC and the exchange and then does its own simplified IPO to raise funds that are held in a trust account. They then seek to merge with a target company in what is known as a reverse merger. The target space firm and SPAC negotiate an agreement that may take a few months and the company can negotiate a valuation and the guaranteed cash proceeds that it requires.

Once a deal is struck, typically the SPAC investment bankers will raise a PIPE (Private Investment in Public Equity) with institutional investors. This ensures that outside institutional investors can vet the transaction and valuation, raising confidence in the deal. Also, the PIPE money, along with the funds in the trust, will be used to meet the minimum cash thresholds needed by the space company.

When the deal is announced, both the shareholders of the target company and the shareholders of the SPAC vote on the deal. In the presentation deck prepared for the transaction, the target is allowed to use forward looking statements. That is not allowed during a traditional IPO, where you are limited to showing audited historical results. Imagine a space company that has had significant upfront CAPEX expenses and is just emerging from the “Valley of Death”. Would it not be advantageous to show potential investors the type of forecasted future revenue and cash flows from all that investment ?

There are concerns that have been expressed by some who consider public stock markets to be a casino, exhibiting irrational behaviour. That the purpose of SPACs and the market in general is only to provide an opportunity to sell overvalued equity to a “Greater Fool” . Personally, I think that fear is overstated. In my view we have had over a decade when too many great companies stayed private, became “unicorns” with billion dollar valuations but weren’t available for the general public to be able to invest in.

There is a great appetite from the public to invest in Space, whetted when they read stories online and see the exploits of companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin. When Virgin Orbit went public via a SPAC in 2019, it received the benefit of this space halo because the public had no other vehicles to invest in. Now there are over a dozen public NewSpace companies that have SPACed, and more will follow.

There has been a study by McKinsey in September of 2020 (here) that made a very astute observation.

One year after merging, operator-led SPACs outperformed both other SPACs (by about 40 percent) and their sectors (by about 10 percent). “Operator led” means a SPAC whose leadership (chair or CEO) has former C-suite operating experience (versus purely financial or investing experience). The findings, while not statistically significant, strongly suggest that operators make a meaningful difference. Operator-led SPACs behave differently from other SPACs in two ways: they specialize more effectively, and they take greater responsibility for the combination’s success.

So just like in choosing the right VC to partner with, if your are looking to go public via the SPAC route, it is imperative to choose the right sponsor team. Celebrities, or large Private Equity or VC led SPACs may not align with what your goals are. The right sponsor team will take a long term approach with you to not only complete the transaction successfully but also provide guidance into being a successful public company and managing the quarterly scrutiny that entails.

Ad Astra !